Demographics and Economic Growth

|

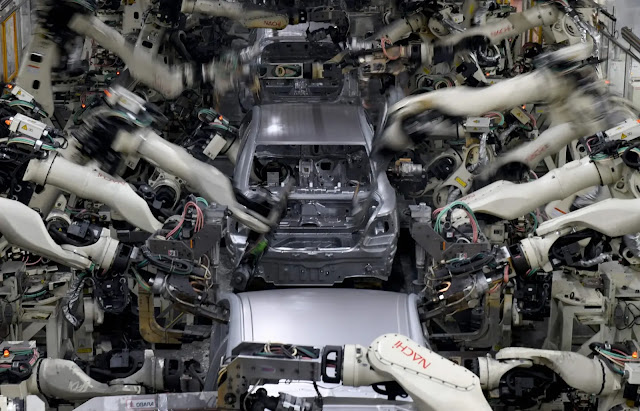

| The Future Manufacturing Labor Force |

SUMMARY

This post is a summary of some of the themes of previous posts on demographic and population projections, with an emphasis on how demographics impact economic growth. See bibliography at the end of this post. For a list of all blog posts on a wide variety of topics, see List of Posts by Topic on my blog.

Almost all countries outside of Africa are already facing or will soon face below replacement birth rates. Without immigration, this could lead first to smaller labor forces with greater numbers of retired citizens. Eventually, however, both the number of workers and retired citizens will decrease. During both stages of the transition, there will be issues of how to increase total output, maintain standards of living, and allocate income between the two major age groups. For background, see Global Demographics and Population Projections.

Population and economies can growth even if birth rates are below replacement. But eventually both economic output and real income per capita fall unless countered by migrations, new technology that increase productivity, or organizational, political and societal change. Societies will have to manage these transitions to avoid economic and political crises.

The first country that has started on the demographic declining path for wealthy nations is Japan. The depopulation curve starts with a slow descent, then accelerating. Japan has until 2030 to prepare for the rapid decrease in total population and the labor force age group. For details, see Demographics and Population Projections of Japan.

Other countries - China, countries in Southeast Asia, and countries in Central Europe - will soon face the same demographic trends as Japan.

The countries outside of Africa will have a collective labor shortage; the countries inside Africa will have a collective labor surplus. Wealthy industrialized or industrializing countries with declining populations will have different problems and strategic alternatives than poorer countries that have above replacement birth rates and increasing populations. For details about global population projections and the demographics of these two types of countries, see Global Demographics and Population Projections.

Immigrants into the wealthier countries will be one way to counter a dwindling labor force. Some of the immigrant will come from countries with declining labor forces. Immigrants will be especially in demand in the “service” sector with rising numbers of older citizens needing medical care and other services. In the United States, immigrants, both legal and undocumented, are also crucial for new construction, farm labor, restaurants, and various service and maintenance industries. But until the labor shortage becomes critical, there will be continuing political opposition to immigration.

An aging population plus increased immigration of different ethnic and religious groups may be necessary for economic growth but also a recipe for political conflict. Aging populations tend to become more conservative, less likely to support change, but more in need of immigrant service employees.

Changing demographics will influence the national and global allocation of labor. Decisions about allocation of labor – outsourcing, immigration - will sharpen the conflict between national policies and the global economy. Corporations have different strategies and objectives then national governments.

Changing demographics will influence the mix of supply and demand. In wealthier countries, more of the economic and political decisions will be driven by the increasing population of the elderly, including public support for health care services and biotechnology research. In poor countries, the economic objective will be how to grow rapidly to employ a quickly growing labor force.

There are three substitutes for a country’s shrinking labor force – immigration, investment in innovation and new technology, and organizational innovation and more productive employees. Better educated and trained employees and researchers are crucial for innovation and economic development. The new technologies of robotics and AI may reduce the long-run demand for the human labor force, especially in areas of white collar data processing and analysis jobs, although both will create new jobs demanding a high skill level.

How will governments and societies cope with the triple problems of declining populations, supporting an aging population and the cost of mitigating global warming?

THE ACCOUNTING IDENTITY OF ECONOMIC GROWTH

The accounting identity here is a framework to explore implications of a shrinking labor force for economic growth and development.

An accounting identity says nothing about causality, assumptions or feedback. But it introduces some general issues.

The following accounting identity shows the sources of economic growth:

The economic growth rate (growth rate of total output) roughly equals the growth rate of the labor force plus the increase in labor productivity (output per member of the labor force).

If the labor force numbers are stable, all of the increase in output depends on the increase in productivity. The pressure on productivity is even greater if the labor force numbers are decreasing. So, for example, if a labor force is increasing at about 1% per year and productivity is increasing at about 1% per year, output will increase about 2% per year. If the workforce stops growing, productivity will have to double to 2% to yield the same economic growth. If the workforce were to decrease at 1% a year, as it is in some countries already, productivity would have to increase 3% a year to achieve 2% economic growth. This is a high productivity growth rate for a developed economy.

Declining population, declining labor force and some increase in productivity could lead to higher standards of living (real income and consumption per person). But the demographic trends, without other changes, might lead to less innovation and lower or negative rates of productivity growth.

Low rates of productivity growth with accelerating rates of labor force and population decline could also lead to less output (negative growth rates) and declining standards of living.

LABOR SUBSTITUTES

A member of the industrial/information labor force today is better educated, with new skills, working with better capital equipment and IT inputs, compared to a member of the labor force a generation or two ago. The difference should show up as an increase in labor productivity. Increase in total factor productivity is due to innovation in capital equipment – including information technology – combined with employees with new skills and knowledge. Other factors included economies of scale, network effects, public investment and organizational innovation.

Capital investment, technological innovation, and organizational change are substitutes for labor. The composition of the declining labor force will change.

2-3% sustained productivity growth is unlikely without a dramatic impact from AI-augmented robots, AI-augmented business software, advances in new energy and production processes, and, possibly, quantum computing. Unit costs and prices are falling for a wide range of new outputs – EVs, solar panels and systems, energy from other renewables, hydrogen, large batteries and carbon capture.

Changing demographics will help direct the actual products and services of the new technology.

Some white-collar, middle-class jobs will be eliminated and replaced by software like AI, which will become more sophisticated in the future. AI programs are already able to analyze large quantities of specialized data and quickly reach conclusions and devise strategies. While AI and other new technologies will create technology jobs there is a fear that for the first time in the history of the Industrial Revolution, more jobs may be eliminated than created by new technology. Labor-intensive manufacturing and white collar data processing may be hit the hardest. One possibility is that high-wage, advanced technology systems may replace labor-intensive economic processes in low-wage countries. The economic disruption may be less if matched by a decreasing number of workers.

The new information technologies may primarily affect white-collar jobs, unlike past industrial technologies that mostly affected blue-collar jobs.

There will possibly be a greater importance of a globally connected and managed economy. Multinational companies will develop and control technology and globally allocate labor and other inputs. This might increase conflicts between the objectives of multinational companies and national governments.

DEMOGRAPHICS AND DEMAND

Demographics also influence the demand side of economies. Americans spend more money on pet products and services than on childcare. In South Korea, which has the lowest birth rate in the world, consumers spend more money on “baby carriages” for pets than for human babies.

Companies use demographic information when planning marketing and advertising strategies. Changing demographics are analyzed when developing new products, changing product mix, and segmenting markets. The explosion of detailed demographic information about smaller and smaller segments, down to individuals, combined with online marketing technology and almost real-time data analysis algorithms, is revolutionizing marketing and advertising.

Companies are using this data and analysis to fine tune pricing strategies such as price discrimination and dynamic pricing.

Autonomous driving vehicles and robotaxis should find a huge demand from older Americans, the number of whom are expected to double in the next 20 years.

IMPLICATIONS FOR ECONOMIC POLICY

In the past, there was a correlation between industrialization and secular increases in population. There were also national and international allocation of labor. A large number of people left Europe between 1815 and 1914, especially at the start of the second stage of the Industrial Revolution around 1870. An estimated 60 million people emigrated from Europe. They opened up new agricultural lands in other countries and provided some of the labor force for the new factories, mines, and railroads. The United States also experienced a large immigration of Latin American and Asian groups, starting in the 1960s. There was also large internal migration within countries. At the same time, the Industrial Revolution created new economic groups including industrial entrepreneurs, industrial work force, investment bankers, and a new technical and managerial middle class. This led to political conflict between traditional elites and the new groups, fights for political power and status. This also led to a call for economic and political reforms - the Populist and Progressive movements around 1900.

The standard economic models demonstrate that the demographic changes we saw over the last 200 years are a function of economic growth and development. Industrializing, urbanizing populations have declining birth rates. The experience of the poorer regions of the world tends to indicate that these demographic changes can occur even without economic growth and development because of imported modern health and the spread of primary education. The challenge for low and middle-income countries now is the danger of “getting gray before getting rich.”

Although wealthier countries concentrate on the costs of their rapidly growing retired population, for most of the world the critical question over the next two generations will be how to accelerate economic growth to provide jobs and opportunity for the growing working age population. The related challenge is how to improve education, training and economic opportunity to raise standards of living now to provide the resources for the aging population in the future.

For the entire world, these objectives are complicated by how to pay for the social costs of past industrialization and environmental degradation, and the future costs of climate change.

Over the next 40 years, the global population is expected to increase by 1.7 to 2.0 billion people, despite below replacement birth rates in most of the world. Although wealthier countries will concentrate on the costs of their rapidly growing retired population, for much of the world the critical question over the next two generations will be how to accelerate economic growth to provide jobs and opportunity for the growing working age population. Part of the challenge is how to improve education, training, and economic opportunity to raise standards of living now to provide the resources for the aging population in the future.

For the entire world, these objectives are complicated by how to pay for the social costs of past industrialization and environmental degradation, and the future costs of climate change. This will be a major part of future investment and a possible source of income and employment, especially for the technically educated.

In the long run, the positive side of declining global population may probably be less demand for resources. It depends on fewer people versus higher standards of living and changing preferences. Combined with substitute technology, global warming might slow down or stop. Climate change might not have quite the devastating effects trend projections indicate.

The advanced and industrialized countries with stable or declining populations and labor forces will have to consider the following:

Economic growth will have to come from large increases in productivity (output per member of the workforce). To achieve this, and also meet social welfare costs, most countries and regions such as the European Union will have to make changes in economic policies. Particularly disruptive and contentious will be the adoption of automated factories and offices. On the positive side they will increase labor and total productivity; on the negative side they will probably eliminate a large number of existing and future jobs. Retirement ages and requirements might change, depending on political resistance.

Even in the United States, a large increase in retirement age populations is leading to potential underfunding of public and private pension funds. Taxes to fund public pension funds are rising, both in amount and as percent of federal, state and local budgets. Despite this, unfunded liabilities – promised future benefits not covered by projected future revenue – are also rising. The $300 billion/year deficit in social security funding after the trust fund runs out in 2034 will probably be paid for by an increase in general government expenditures.

The United States is already experiencing large yearly fiscal deficits and a very large and rapidly-rising national debt. For the present and future impact of these trends on federal government budgets, see

Government Finance 101: Fiscal Policy. Can't Anyone Add?

Multinational corporations will develop and adopt the new technology. Countries that do not have quality education, invest in public infrastructure, fund scientific research, encourage innovation and change economic incentives will not be able to attract foreign and domestic investment and compete in the global economy. And their best educated and most motivated people may emigrate.

On the other hand, poor countries with decent transportation, energy and communication infrastructure will probably attract foreign investment. Real wages of at least part of the labor force will rise.

Attitudes towards immigration might change from the current restrictive policies of some countries. Attracting “human capital” will be just as important as attracting investment capital. Trans-border movement of people will increase. New national, regional and international agreements will have to be negotiated. Remittances back to the home country will be a more important part of the economy of many countries and global capital flows.

Attitudes about work, labor laws, retirement and retirement ages will change. The benchmark age of 65 was arbitrarily set by Bismarck almost 150 years ago when a very small percent of the German population lived that long. When the United States adopted Social Security, life expectancy was 56 years. The life expectancy of America’s younger workers is already around 80 years.

The Japanese government and elites seem to have accepted declining population, slow (if any) economic growth, social stability and rising per capita income. They are increasing immigrant labor but there is a limit. They will export capital, earning income from overseas investments. They will outsource production of Japanese companies and export manufacturing technology, including robots. Whether all industrialized, wealthy countries can adopt the same policies at the same time seems unlikely.

What is uncertain is whether or not the Japanese government can continue to fund domestic expenditures by running large deficits. Global interest rates were low until 2022. This assumes that Japanese are willing to lend their savings to the government. Maybe part of an implicit social contract that the money will be spend on services for the elderly.

Other countries facing a “Japanese future” do not have the resources (per capita income and tax base) that Japan has. Many other countries do not have the political and cultural stability that Japan has. Hardly any country realizes this is soon going to be their number one domestic problem.

Countries are already facing the domestic problem of needing more immigrants to augment the declining labor force in the face of rising opposition against immigration. Without immigration, some countries will be facing declining output and lower standards of living. This will probably increase domestic anger and stresses. Rather than Japanese stability, there will be further instability fueled by increasingly shrill populist, nativist politicians.

More people will see they are living in a “zero-sum” country where more domestic resources will have to be allocated to a rapidly increasing older population It could be that political battles will be fought over age-based “income inequality.”

If taxes on the working population go up, this might further discourage economic development (innovation and risk-taking) and growth. The exception may be for products and services aimed at senior citizens.

Demographics are heavily influencing the areas of investment in wealthy countries; these sectors will drive future economic growth. Three current active areas of research and net investment are robots and AI (reaction to declining workforce), autonomous driving and robotaxis (aging population) and biotechnology (aging population).

How will governments and societies cope with the triple problems of declining populations, the cost of mitigating global warming, and supporting an aging population? With dysfunctional societies and governments, large and growing budget deficits and national debts, opposition to immigration, on top of existing political, ideological and economic problems?

The solutions may have to be global. This suggests increasing conflict between national governments (and their power elites) protecting privileges, national identity and sovereingty. This appears to be happening in the European Union. Maybe national governments can by replaced by international organizations whose members are not national governments. Some possible alternatives might be multinational corporations and privately-funded NGOs.

Fighting global warming, especially reducing the burning of fossil fuels, may pose an economic threat to poor countries dependent on “extractive” industries. Developing and poor countries whose economies depend on exporting raw materials – fossil fuels, minerals, agricultural goods – may have a particularly difficult time.

Increasing population and rising real income in emerging economies, especially in Asia, are increasing the demand for energy. A dramatic increase in the number of cars in Asia is the main reason for the continuing increase in global demand for oil. Increased demand for electricity is being partly met with new power plants burning fossil fuels. For at least another generation, these trends will make it difficult to meet global goals to drastically slow down or stop global warming.

DEMOGRAPHICS AND DEMAND

Demographics also influence the demand side of economies. Americans spend more money on pet products and services than on childcare. In South Korea, which has the lowest birth rate in the world, consumers spend more money on “baby carriages” for pets than for human babies.

The large increase in the Hispanic population in the United States has created a demand for new types of food and restaurants, new source of popular music, Spanish language TV and radio, bi-lingual teachers, imported beer, shifts in airline travel, and higher income remittance services. Chili is the go-to food at many Super Bowl parties.

Companies use demographic information when planning marketing and advertising strategies. Changing demographics are analyzed when developing new products, changing product mix, and segmenting markets. The explosion of detailed demographic information about smaller and smaller segments, down to individuals, combined with online marketing technology and almost real-time data analysis algorithms, is revolutionizing marketing and advertising.

Companies are using this data and analysis to fine tune pricing strategies such as price discrimination and dynamic pricing.

An aging population has increased demand for health care, retirement communities, RVs, leisure activities such as cruises, robot companions (in Japan), and reverse mortgages. Autonomous driving vehicles and robotaxis should find a huge demand from older Americans, the number of whom are expected to double in the next 20 years.

South Korea has the lowest birth rate in the world. Sales of “baby carriages” for pets is greater than sales for human babies.

DEMOGRAPHICS AND SUPPLY

If there are labor shortages, the result may be larger salary increases. Corporations may then step-up investment in labor-saving technologies, especially if immigration in the wealthier regions is limited by the political backlash.

The shortage of workers may accelerate the development of robotics and AI to substitute for workers. Economic growth will depend more than in the past 250 years on economic development, innovation, new technology and productivity increases than on population and labor force growth. The quality of workers – their education, skills and knowledge – will be more important than their numbers.

Demographics will change attitudes about retirement, immigration, employment and unemployment, automation, work and leisure, and economic growth. Retirement programs may be especially strained as the ratio of retired people to working people goes up.

DEMOGRAPHICS AND FOOD PRODUCTION

Demographics is interacting with climate change in another important area – food production. Many scientists believe the most serious effect of climate change will be its impact on food production.

Global warming and more extreme weather events will make it more difficult to expand food production using current technology. As in other areas, trend projections can be changed by the development of new technology such as drought-resistant strains of grains.

The global population will include about 1.7 to 2.0 billion more people between now and the 2060s. The challenge here is how to feed them, on top of rising food consumption per capita in emerging economies and possible negative effects of rising temperatures on food production, especially in tropical areas.

Technology is a substitute for using more land. Yields per acre have gone up dramatically in the last 75 years. In the U.S in the last 100 years, tractors eventually replaced about 23 million horses and mules. About 60 million acres of cropland planted to feed the horses and mules were freed up. Farms became larger and reduced the number of workers needed to produce food. (The Economist, “A Short History of Tractors in English,” December 23, 2023, 20-21.)

Expanding agriculture, and highly productive modern agriculture, are now a threat to the environment and a cause of climate change and environmental degradation. Examples are the burning of tropical forests, depletion of aquifers, and heavy use of fossil fuels to run machinery and produce nitrogen fertilizer and farm chemicals.

Food producers in industrialized areas may find that declining populations mean lower sales. But exports to poorer regions with increasing populations may rise.

SPECULATIONS AND SUMMARY

Static or declining labor forces outside of Africa mean economic growth will mostly depend on increases in productivity. To counter demographic trends, technological innovation leading to high rates of productivity growth will be necessary to increase standards of living (real income per person).

Rising population in poor countries make high rates of economic growth both pressing and difficult. Emigration pressure from poor regions of the world will probably increase unless there are high rates of economic growth in poor countries.

Most of the world’s population increase will take place in cities and surrounding metropolitan areas, creating even larger massive urban areas. Large urban areas are increasing rapidly in poorer countries.

It is nearly impossible to predict technological and organizational change over the next 25 or 50 years. This will help determine if increases in productivity will counter the decrease in the size of the working population.

Demographics interact with global economic and environmental trends. More people mean more food and more consumption products and services, which means more energy and technological inputs. At the same time, new technology must reduce carbon-emitting energy and production processes.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

DEMOGRAPHICS AND ECONOMICS

I believe that projections and related analysis of demographics should be the starting point of any long-range planning. There is time to implement strategies that mitigate the probable negative impact of these trends. For the data, see

Global Demographics and Population Projections

The United States may be one country that avoids experiencing declining population and labor force. For details on how this may be possible, see

Demographics, Immigration and Future Economic Growth of the United States

Japan is already on the declining labor force and population curve. It also has the world’s oldest population. For details, see

Demographics and Population Projections of Japan

For a case study of the difficulties of an African country trying to develop, see

For a discussion on why England and America had the prerequisites to start the Industrial Revolution and continued to economically develop, see

THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION IN ENGLAND

The Beginning of the Industrial Revolution in England

Josiah Wedgwood, the Wedgwood Pottery Company, and the Beginning of the Industrial Revolution

A Cautionary Tale - England and the Industrial Revolution

AMERICAN ECONOMIC HISTORY

The Beginning of the Industrial Revolution in America

How America Industrialized and Became Wealthy

Alice in Wonderland and the Origins of Silicon Valley

AMERICAN HISTORY

The classic book on colonial immigration is David Hackett Fischer, Albion’s Seed. For a much shorter study of colonial American immigration, and an introduction to some long-term consequences, see

American Colonial History, 1607-1775

For a case study of a country (multi-national empire) undergoing industrialization, internal migration, the rise of new classes, and heightened social and political tensions, see

The Austro-Hungarian Empire Before World War I

Comments

Post a Comment